Oaxaca de Juárez. “What’s this small bone? Is it from a chicken or a hand?” asks one of the women searching for her relatives in a dump of food refuse in the Central Valley of Oaxaca.

“Let me see,” says her colleague and drops the shovel with which she has been digging.

They both stare for a moment at the bone and compare it with those of their own hands.

“No,” concludes the second woman, “this is definitely a chicken bone. Leave it there so that the others can see it”.

It is the 13th of August 2021. Eight women and two men, members ofSabuesos Guerreras, a non-profit helping rastreadoras or searchers for disappeared people, are participating in the first of a series of “Search Days” organised by the recently created State Commission for the Search for Missing Persons of the State of Oaxaca. Equipped with boots, hats and clothing to resist the scorching sun, they also wear facemasks and carry hand sanitizer to prevent themselves from getting covid-19. Today they arrived at sunrise in three vans packed with pikes, shovels and metal rods; all of which they have had to source themselves.

On the third day of the search, they receive news that they will no longer receive protection from the National Guard, which for the last two days has escorted them to the gullies and rivers as they conduct their work. The State Commission for the Search for Missing Persons will no longer stay with them either. Today, the responsibility for scouring and digging over the area has been left to the rastreadoras: mothers, wives and daughters who have been forced to search for their loved ones on their own. Although the group is formed mostly by women, there are also some men.

“Who are you looking for this time?” a journalist had asked them some days ago at an event in which the Search was publicly announced. “We’re searching for them all,” the group replied without hesitation.

Claudia Uruchurtu

The latest case of politically motivated, forced disappearance in the State of Oaxaca is that of Claudia Uruchurtu Cruz, a 48-year-old woman. She was disappeared from her hometown, the town of Nochixtlán, in the Mixtec region, but before that she had documented and denounced nepotism and corruption in the municipal government run by the mayor Lizbeth Victoria Huerta. On the night of the March 26, 2021, Claudia participated in a peaceful demonstration in the centre of Nochixtlán. After that, a group of unknown men forced her into a red van. Her whereabouts since that day remain unknown.

Elizabeth Uruchurtu Cruz explains to Corriente Alterna that her sister, Claudia, had been documenting the corrupt diversion and mismanagement of public funds by the municipal government under the administration of Lizbeth Huerta, who throughout 2021 has been aggressively campaigning to become re-elected. Before her disappearance, Claudia had visited her sisters, both of whom live and work in the United Kingdom. However, in the run-up to the 2018 presidential elections she returned to Oaxaca as she was determined to cast her vote for Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). “‘Please stay a bit longer’ we said to her, ‘the summer’s just about to begin,’” remembers Elizabeth, her sister. But she insisted on going back to support López Obrador because she was convinced that as soon as he became president, things would begin to change.

On the first of July 2018, just as AMLO was elected president of Mexico, Lizbeth Victoria Huerta was elected mayor of Asunción Nochixtán, as part of a coalition including MORENA and the Workers Party (PT), both center-left parties, and the far-right PES (Social Encounter Party). The coalition called itself: “We’ll make History Together.” For Nochixtlán, this was an important election. Not only was it the first time a woman had become mayor, but it was also the first time the town had been ruled by a party other than the Party of the Institutional Revolution (PRI).

Nevertheless, very little changed with the arrival of MORENA in 2018. Elizabeth sums up the story like this: “when the new administration took office, Claudia noticed that, instead of investing in making the town better, they were wasting it on foolish things. It was then that she started to denounce what she could see happening.” Indeed, Claudia noticed that once Victoria Huerta had control over the municipal government, some relatives of the mayor were seen around town boasting brand new motorcycles and others were appointed to posts in public offices. The mayor herself was spotted wearing a wrist-watch worth more than a 160 thousand pesos (almost £6000), among other luxury items.

Claudia denounced all of these irregularities using the official channels at municipal, state, and federal levels of government. She issued official complaints to the Internal Organ of Supervision of the Town of Nochixtlán, the Secretariat for the Supervision and Transparency of the Government, the Supreme Auditing Office of the State of Oaxaca, the Congress of the State of Oaxaca, the General Secretariat of the Government of Oaxaca, the Secretariat for Home Affairs, and the Attorney General of Mexico, among others. She received no clear response from any of them.

“Claudia never thought of herself as an activist because, in her view, she believed that everyone should do what they could to fight for their rights. She simply saw it as everyone’s responsibility, something that had to be done to improve the living conditions [of ordinary people],” says her sister. “I think what happened was that an audit was carried out and pressure was placed on the municipality. Around that time, the municipal authorities must have begun to feel uneasy about Claudia.”

MayorLizbeth Victoria Huerta was arrested on May 7, 2021, together with two collaborators accused of forcibly disappearing Claudia Uruchurtu. Two additional people were detained on July 22. Currently all three are awaiting trial. The hearing of the defence took place on Wednesday, October 13.

Elizabeth accepts that the attention the case of Claudia Uruchurtu has received is unusual in comparison with the impunity that prevails in most disappearance cases in Oaxaca. The Mexican office of the United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights (ONU-DH), the UN’s Committee on Forced Disappearance, Amnesty International and British MPs have all raised concerns regarding the case. “We have had the chance to talk to authorities, which most people don’t get. This situation is extremely sad. It shouldn’t be like this.” Yet, in spite of everything, Claudia Uruchurtu remains disappeared.

The magnitude of impunity

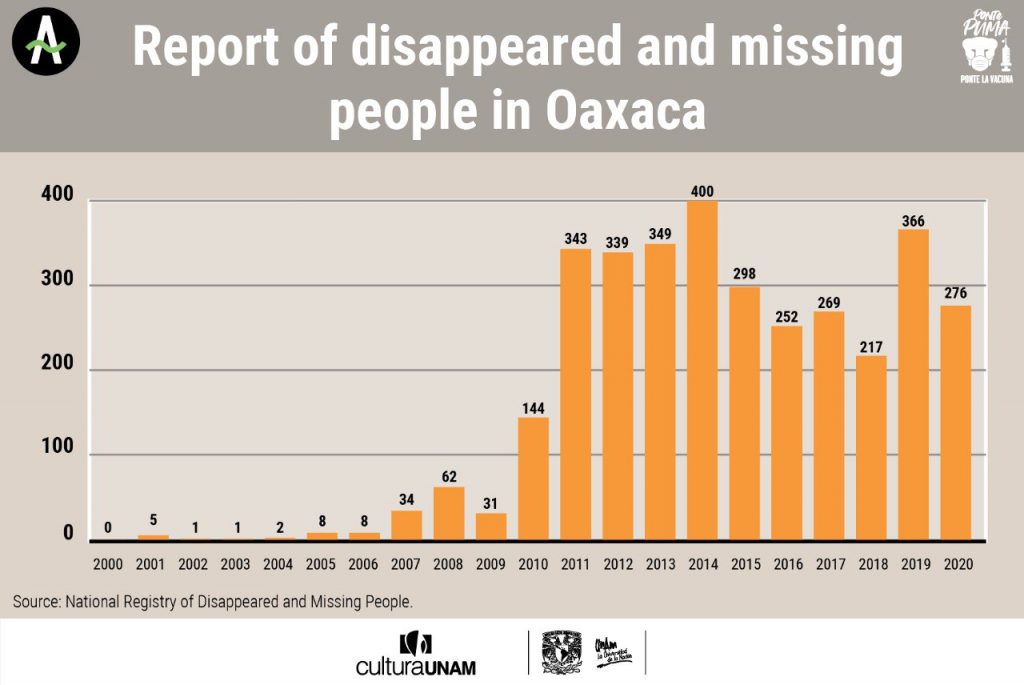

According to the National Registry of Disappeared and Missing People, 3,629 people have been reported disappeared or missing in the state of Oaxaca since 1964, with 90% of cases occurring during the last 10 years under the governments of Gabino Cué Monteagudo (2010-2016) and Alejandro Murat Hinojosa (2016-2022).

Of these, 362 people are still disappeared or have not yet been found. In addition, several NGOs and independent organisations have shown that the true figure is much higher. For instance, the Platform on Feminicide and Violence in Oaxaca has documented more than 1,415 women who have been disappeared during Alejandro Murat’s administration alone.

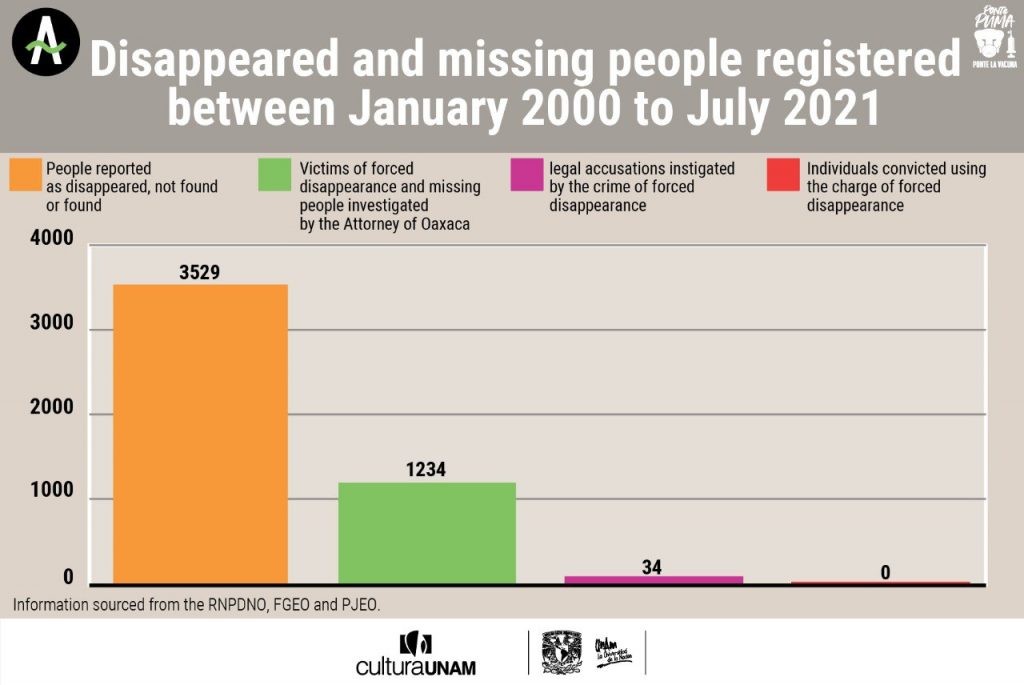

Furthermore, over the last two decades (between the year 2000 and July 30, 2021), only 35% of cases of people reported missing, disappeared, or found are being investigated by the Attorney General of the State of Oaxaca, according to the institution’s information.

At the same time, the State Department of Justice reports that in the last 21 years, they have only initatied 34 cases of forced disappearance and not one of those has resulted in a guilty verdict.

At present, there are more than 92,000 people disappeared or missing in Mexico.

Learning How to Become a Rastreadora

Sabuesos Guerreras AC is one of many organisations searching for disappeared people in Mexico. It was founded in the state of Sinaloa by María Isabel Cruz Bernal, mother of Yosimar García Cruz, who was disappeared in Culiacán on the 26th of January, 2017.

In 2020, the organisation began to work in Oaxaca. Six of their members travelled south to offer training to other searching mothers. “Four years and six months after the organisation was created, we have counted more than 180 bodies. We have found more than 18,000 charred fragments and keep finding more,” explains Cruz Bernal.

It was thanks to the support of the mothers of Sinaloa that Oaxacan searchers managed to create their own branch of the organisation, which is now called Extensión Oaxaca. Marta Pablo Cruz is their representative; she is searching for her son, Jassiel Vladimir Florean Pablo, who was disappeared on May 21, 2019 in Tlapa de Comonfort, a city in the state of Guerrero.

María Isabel and Marta share two things in common: both were born in Oaxaca and both are committed to finding their disappeared sons. Similarly, the rest of the members of their group are searching for their relatives. They carry their pictures with them at all times and say their names: Félix Arturo Ayala Tamayo, José Manuel Macías Mendoza, Ángela Sánchez Cruz, Miguel Enrique Cárdenas Echavarría, Luis Alberto Hernández López.

The alliance between Sinaloan and Oaxacan families began taking shape in early 2020, during a workshop in which they shared experiences of searching for the disappeared. It was formalized in September that same year, with Marta being chosen as general coordinator for the Oaxaca region. Marta explains that Sabuesos Guerreras of Sinaloa taught them how to communicate with civil servants and how to request access to the investigative files on their sons and daughters (which they still haven’t received), as well as to push for progress and issue complaints to both state and national human rights commissions.

Whenever possible, rastreadoras support and accompany each other, going together to the attorneys’ offices and waiting outside for one other, often well into the evening. “This kind of affection, this support… I often have more in common with them than with my own family. They have become my sisters, we’re bound by enduring the same pain; they are wives, mothers, sisters who continue to search.”

As soon as they reach the entrance to the dump, the rastreadoras of Sinaloa, grab picks, shovels, sieves, metal rods, portable radios, and whistles from the van. They also set up a drone for air exploration. They explore the surroundings in groups: one sets off to explore the area designated for animal carcasses, the other goes farther, to the stinking stacks of organic waste, which give off an almighty rotten stench.

Sinaloan rastreadoras teach the Oaxacan branch how to identify possible mass graves in areas in which the vegetation has changed or where the soil has sunk in as a result of digging. They teach them how to clean the area, how to dig, how to use and smell the metal bars, which after being inserted into the ground are sniffed to differentiate earthy smells from the peculiar stink of decomposing human bodies. They share with rage and love the knowledge and experience that they have accumulated after years of searching for their own tesoros or “treasures,” the word they use to refer to their missing loved ones.

“Don’t you get sad when, after an entire day of searching, you’ve found nothing?” asks one Oaxacan man who is learning how to distinguish the odours of the earth as part of the search for mass graves and who is surprised to see that the women of Sinaloa do not lay down their tools even when on their break. “We get sad when we do find something,” answers one of them, without ceasing work.

What the Mexican State is still not doing

Soon after the forced disappearance of Claudia Uruchurtu, the federal authorities appeared to do due diligence at the start of the search by requesting the collaboration of the Attorney General of the State of Oaxaca, as well as the Secretariat of Government of Oaxaca.

The administrative offices of the local government were also quick to send support in the form of secretaries and office workers who carried out preliminary fieldwork.

According to Elizabeth, this development was deeply concerning as it revealed the improvised nature of search, which was conducted neither by trained professionals nor in line with judicial and scientific investigation standards. “It’s so sad for us to see such a waste of funding and resources,” she says.

“Also, if there is no way to carry out a search based on the results of an investigation, then why the hell bother coming all the way here? It is as though they lifted a finger in the air and randomly decided ‘hm, OK, let’s search over here or over there,’ and then, of course, the National Guard arrives, with search dogs and all these other people.” It is, in essence, a blind search. Moreover, resources are lacking precisely where authorities have no interest in pursuing these cases, as previously demonstrated with regards to Sabuesos Guerreras’ Search Day in the dump.

Making room for hope

By the end of the day the Sabuesas Guerreras have raked over the entire area. “I know it seems as though we have not done anything at all, but we have achieved a fucking lot,” says one of them, during a final gathering at the entrance of the dump. They have spent exhausting hours under the hot sun, cracking open the earth, and with each strike of the shovel, they make room for a little hope. Standing in the middle of waste and decaying matter, they are visibly nervous as vans pass them along the nearby road. They never forget that searching for the disappeared is a dangerous job. It is also a job that they should not be doing; years and years of governmental negligence and contempt has left them with no other choice. “If we don’t search for them,” they say, “nobody will.”

* The London Mexico Solidarity group has made this translation as a collective effort to support the campaign for justice for Claudia Uruchurtu, and as part of the actions made for the visit of a delegation of the EZLN to the UK.